|

As I reflect upon the content shared in Chapter 9: “Planning for Learning,” from the book Understanding by Design, the idea that most presses me is the authors' call for the following: genuine application to meaningful, real-world problems, hands-on opportunities to “do” the subject, and soliciting and offering helpful feedback along the way. I agree, that is how I want to design my units. But sometimes the most challenging aspect of a executing a unit is student engagement (getting students to want to complete the tasks presented to them)--probing them toward getting lost in the subject so much that they forget that it is work—that is how I feel when I am engaged (the time passes without me knowing). And as the authors point out, this requires students to be self-disciplined, self-directed, and able to endure the challenge of delayed satisfaction.

High aims, right? Am I even able to practice these on a consistent basis? Hmm…not always! But I believe the greatest challenge to these three ideals, when considered components to engagement in the classroom, is that we teachers forget that self-discipline, self-direction and the ability to wait for gratification must be taught. I know I am guilty of simply expecting student to know what these three desired character qualities look like in practice. But when you really look at these words and examine the world in which we live, they are quite counter-cultural to the teenage experience. Does that mean we should just accept that, no? In my home and in my classroom I don’t desire to train my children to just blend in—joining the status quo. Absolutely not. I want so much for them than that. I want them to be highly-motivated, kind-hearted, agents for change in a world that so desperately needs people of such quality. But I must step back and realize that they just might not know what that looks like. That I might have to, in the midst of focusing on content, focus too on the instruction of character qualities that will enable my students to become engaged through the way they act and think.

Wow, and doesn’t that sound like a daunting task? I think going back to just teaching English like its just another school subject sounds like a huge time saver. But if you read about my work as an Under Cover Agent, you will know I am not about saving time and I like a good alias. So I will press forward in my work, using the boring subject of English to transform students’ character qualities, not just their understanding of the literary world.And I will try my best to do tgenuine application to meaningful, real-world problems, hands-on opportunities to “do” the subject, and soliciting and offering helpful feedback along the way

5 Comments

In chapter 7: "Thinking Like an Assessor," in the book, Understanding by Design, by Wiggens, Grant P., McTighe, Jay the authors challenge educators to veer way from being activity planners, toward first determining what concepts need to be assessed, then creating real-world-like assessments in which students are able to authentically work through and reveal understandings that align with the forementioned concepts. From this reading and my own personal experience with putting Backwards Design into practice, i offer:

My Top 10 List - “Thinking Like an Assessor” 1. RUBRICS: clearly aligned with big ideas. Use the rubrics often throughout the unit. Put them in the hands of the students so that they are also using them to evaluate their understanding throughout the unit 2. Focus on how to establish and assess transferability of knowledge and skills, based on big ideas (essential questions) 3. Examine planned formative and summative assessments to ensure that each provided evidences that align with goals of the unit 4. Include frequent practice (through formative assessments) for students to compare and contrast and summarize key ideas 5. Effective assessment is more like a scrapbook than a snapshot. Collecting evidence over time will lead to a clearer picture of achievement toward the goal 6. Provide many formative assessment opportunities 7. Create Real-world situations-->where students are able to Uncover the problem/situation-->using relative Real-life contexts 8. We need to know the learners’ thought processes along with their answers: Why-->Support-->Reflection 9. A student who really understands…

10. Reflection from beginning to end of unit:

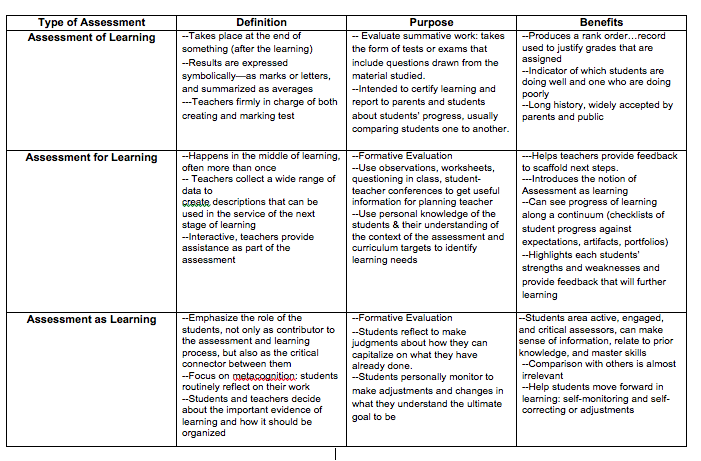

As a high school teacher I feel that the above are reasonable and valuable aims in the making of assessments. I believe the most powerful ingredient is including the students in the process of assessing. But I wonder, is the same possible at the middle and elementary school levels? Especially, the ability to "see in perspective" or "reveal self-knowledge". I would tend to think that a certain level of cognitive and emotional development would be needed that might just be too much to expect from students in lower elementary. Would you agree? Why or why not? Who knew teaching was going to be so much more about assessing than about teaching? Really, you can write some pretty awesome, interactive, engaging, and content explosive curriculum, but if you don't know how to assess what the students turn in to you, how are they or you going to know what amount of learning has taken place? It is so true. How often have you gotten to the end of a unit, collected a final assessment, and were paralyzed as you stared at the stack of artifacts needing marking because you realized you didn't actually know exactly what you were looking for in the assessment? It has happened to me. Not always at the end of a unit, but certainly at check-points during a unit of instruction. Through the years I have adapted to a more formative approach of assessment--experience can be the greatest of teachers, right? And if experience is the path that leads me to greater understanding, why do I so frequently forget that the same is true of the darling faces staring at me? Why do I not whole-heartly revamp my lessons to turn over the experience of learning from being completely controlled by me, to being in the hands of my students? I think the answer to that is lengthy and full of excuses, but the three that are highest on the list are: 1) Assessment for and assessment as learning are processes of learning that can be hard grasp, define, understand, or place tangible outcomes to--leaving it hard to explain others. 2) Assessment for and assessment as learning are processes that can look different from student to student, class to class, causing anxiety for those of us who want to know exactly what is going to happen from day to day in our classroom. 3) Assessment for and assessment as learning take T-I-M-E, both in planning and executing. But experience has also taught me that facing the challenges and excuses are worth the effort. And the writing of Loran Earle confirms this. She succinctly defines these assessments, providing definitions, purposes, and benefits. In Chapter 3, "Assessment of Learning, for Learning and as Learning" (see attachment below), Lorna Earle helps to bring a better understanding of the importance and impact of using assessment applicably to the stages of learning that take place during a unit study. The clarifying of Assessment of Learning, vs. Assessment for Learning, vs Assessment as Learning, lead to a better understanding of differing purposes and outcomes of each from of assessment. As a quick reference I have created the below chart: (based on Earle's text) I think the greatest obstacle I needed to overcome in order to create learning through assessment, was to shift my thinking. I needed to let go of the idea that everything that students created needed to be evaluated and graded. I thought that if I didn't do this, they wouldn't do their work. But doing their work and learning are not synonymous--so, I learned. I also had to learn that learning was the goal, not recording of letters and numbers in a grade book. Thankfully, I was in a teaching environment that pushed me toward separating out formative and summative assessments. To value both, to incorporate both, but to focus on the process and place only those assessments that were summative in the grade book, while still recording the formative work to have as evidence of progress (and perhaps as motivation for completion). I still have a lot to learn and practice in regards to adopting assessment as learning practices (letting the learning fall into the students' hands seems so scary and unpredictable at first). But the more I read texts like Earle's the more I am motivated to continue forward in the process of learning to engage the learners in their own journey of learning. Questions for thought:

Question: What wells up fear in an English teacher's blood, nearly paralyzing her from moving forward in life?

Answer: Writing for others to read! Seriously, those of us in the this wonderful world of word-smithing don't always practice what we preach. But sure shootin' we know what we preach and as soon as our fingers hit the key board and we are expected to poor out meaningful sentences and crisp, to the point words for all the world to see, we wonder, Oh, my goodness what judgement did I bring on myself by putting words out there that are formed together in incomplete thoughts, with incorrect punctuation and without evidence of smooth-flowing, cohesive ideas? Its enough to bring on a mini-panic party in one's head, requiring a small pep-talk prior to hitting that dreadful "publish" button. How often do I tell my students, Writing is about getting your ideas down. Don't worry about the conventions, the flow, the presentation. Just get your ideas out there and worry about the rest later. Let me tell you, OFTEN! And if I could I think of a way to do it, I would set text message alerts to be sent out to my students daily reminding them, Just write! Don't worry about it being right! And then those lovely words could be associated with whatever obnoxious alert bell they have attached to their social life. But honestly, when I sit down to write and I know that my words are going to be shared with others, especially those in the field of education or those who know I am supposed to be good at grammar, organization of ideas, specific support, in-text citations (For the love, who came up with all those rules, anyway?), I freeze-up. True confessions, it took my 5 hours to write one section (4 pages) of a rough draft for my most recent research paper! And I would love to say that the following sections went more quickly, that I was just a little rusty after having been away from the actual act of research writing (teaching research writing has been more my mode lately). But alas, it is not true! Every blimey section has taken me at least 5 hours and left me wondering, what in the world I saw in writing when I started on this career path. I mean really, wouldn't pulling your eye brows out with a tweezers be more appealing than spending 25 hours on research paper ROUGH DRAFT? At least with the former the pain is at most 20 minutes--not 25 hours! So why do we English teachers do this? Why do we preach to our students about the beauty and importance of the process of writing? Why do we force, err, I mean, engage our students in this treacherous process of penning ideas to paper? Why do we believe it is good for them? I believe it is because, in the end, we know that just because a task is challenging, and possibly produces fear and anxiety, doesn't mean it shouldn't be done. Such a process (one that is challenging and fear-invoking) whether it be in the classroom, on a court or in a neighborhood, produces strength, accomplishment, determination, and quite possibly meaningful relationships others. In the English classroom it produces an artifact that reflects a student's progress of learning. And what could be more beautiful than to stare at a set of paragraphs that shows the original thoughts of an individual who took a unique journey down a scary path, to find that they had ideas that mattered and were worth sharing? So in fear, I will continue to write for others, but I will also remember that no matter what others think of what I write, I have done something courageous. I have taken a journey down a scary path to discover what I have learned. And in the end I will have an artifact that documents a process that, though painful at times, brought me to a new understanding of a subject and of myself. "And that has made all the difference." |

Jaclyn LoweenEDUCATION Links to all the, Go and See Study, sessions.

Archives

June 2018

|

||||||

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed